NanoAOD datasets

Last updated on 2024-07-29 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How do we find a specific nanoAOD dataset?

- How to we explore the content of our nanoAOD dataset?

Objectives

- Know how to find nanoAOD datasets

- Know how to explore the content of nanoAOD

Find and explore a nanoAOD dataset

Let’s find and explore a particular which we will get even further into later: simulated Z’ events in which the Z’ decays to a top and antitop quark pair.

Callout

A Z’ (“Z-prime”) is a hypothetical heavy gauge boson that could come from extensions of the Standard Model. A review of searches for the Z’ can be found here

Find the dataset

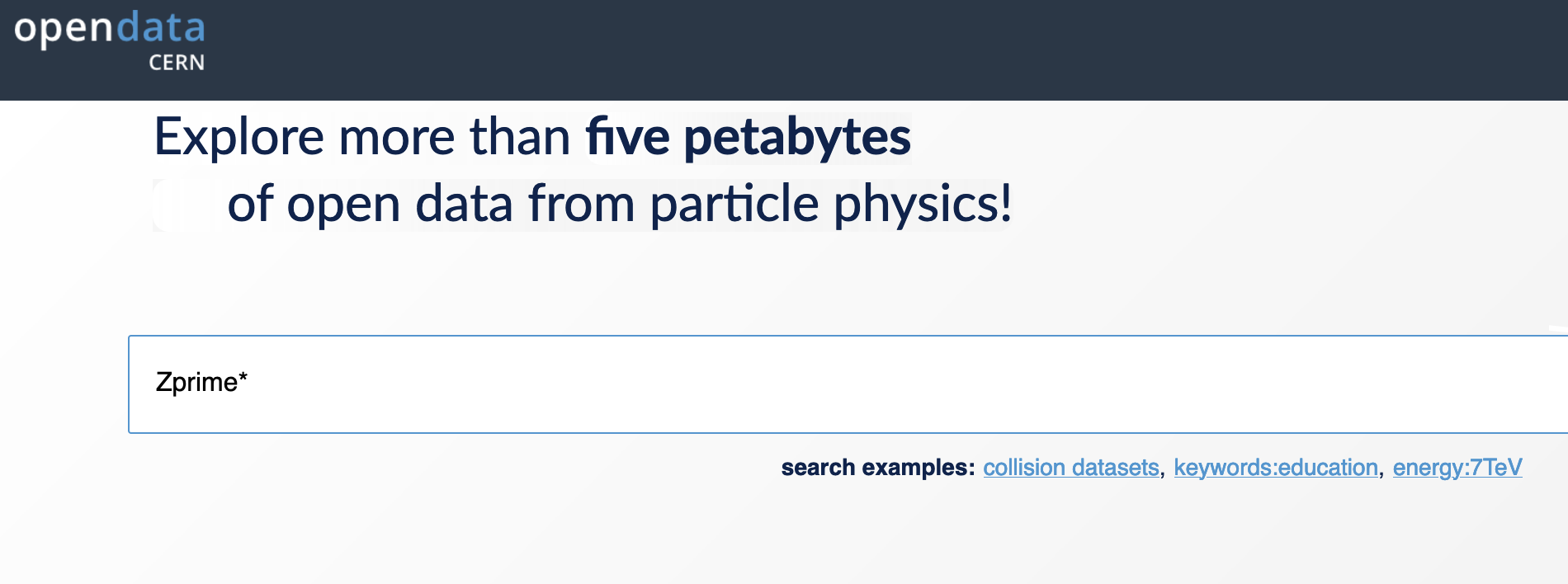

All data can be found via the CERN Open Data Portal. Let’s go to the website and search the simulated Z’ datasets.

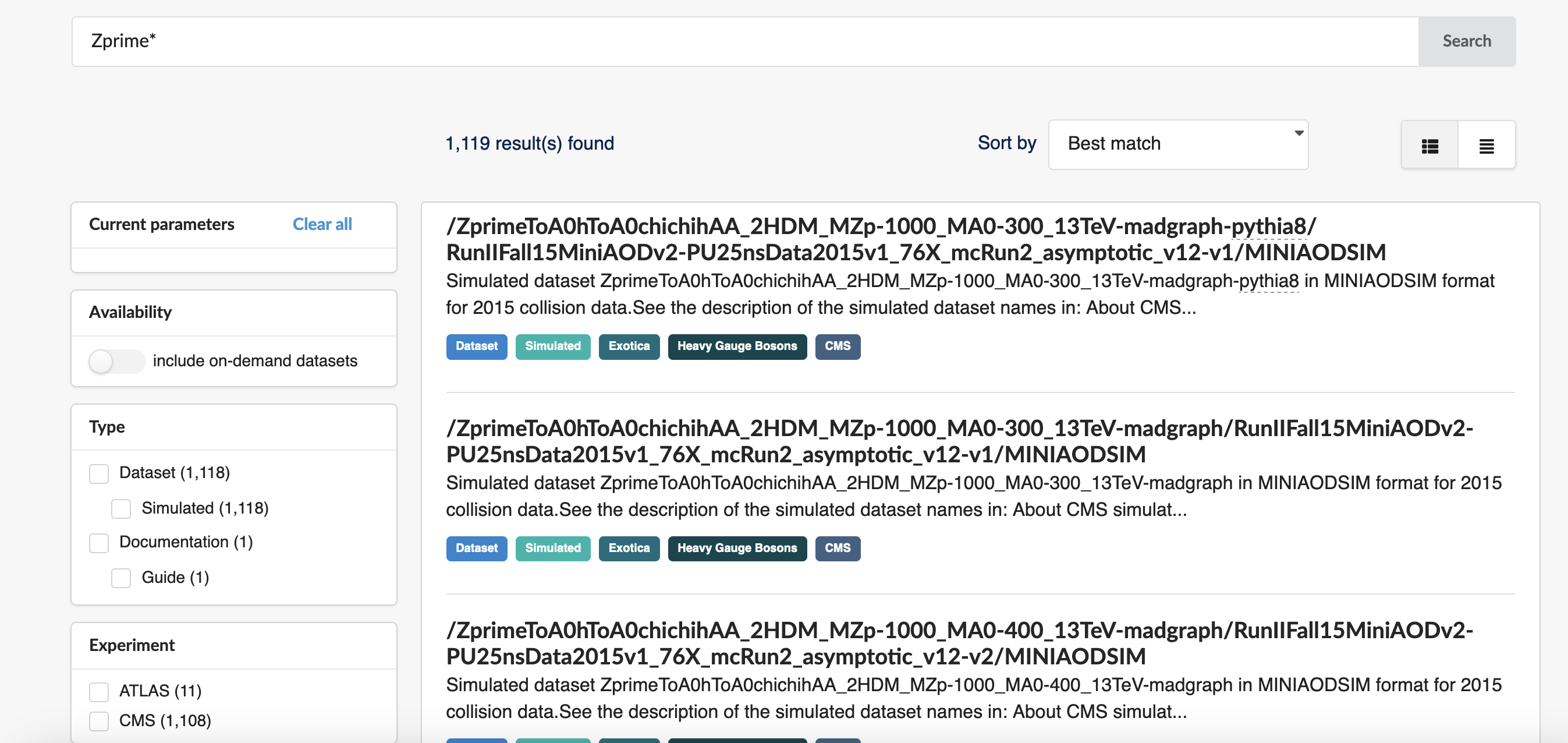

Dataset naming in CMS can seem obscure but let’s do something simple and search for “Zprime*“:

The query results are here and you can see that there are many (over 1000) records returned:

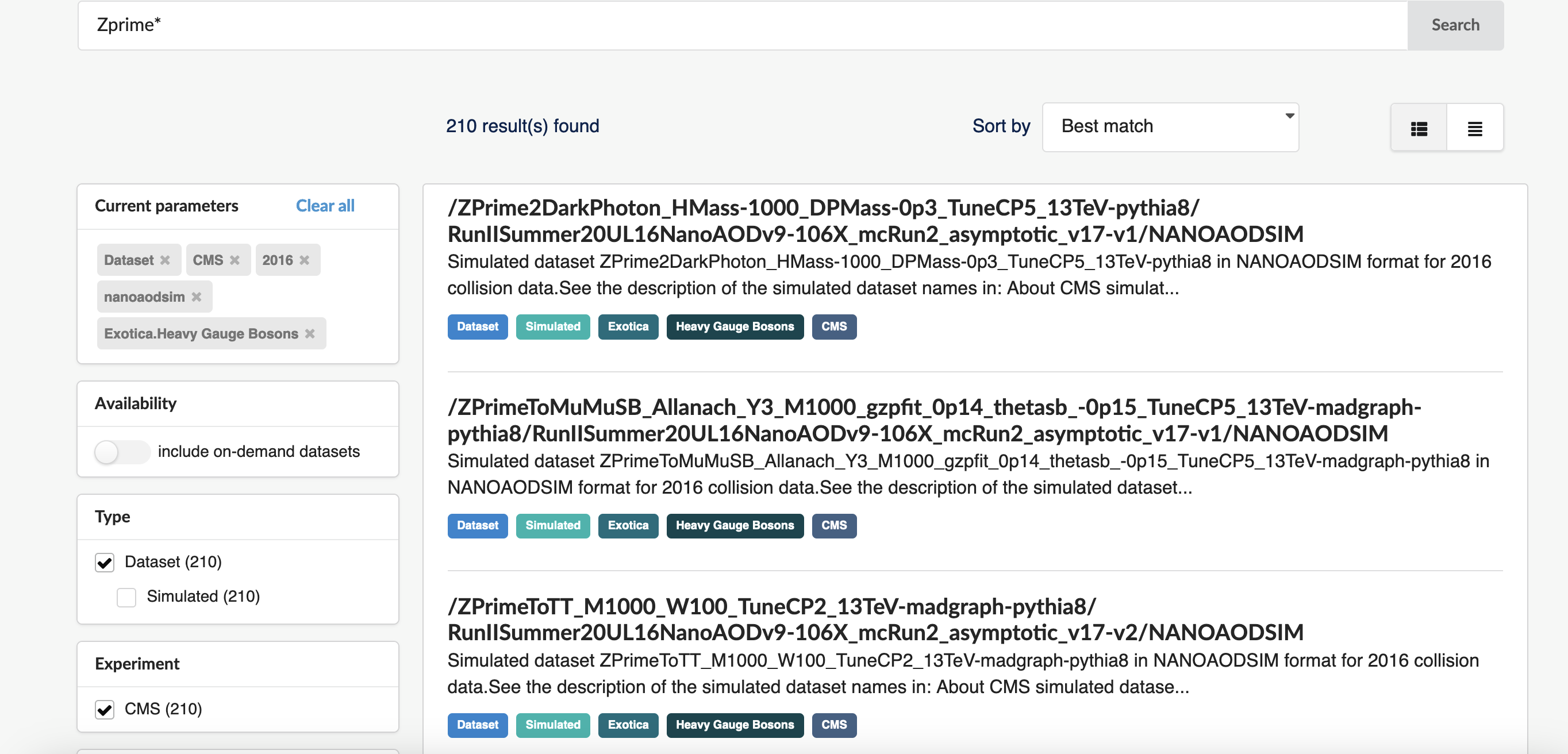

Let’s narrow down the results and select Dataset under Type, CMS under Experiment, 2016 under “Year”, nanoaodsim under File type, and Heavy Gauge Bosons under Category. We’ve now reduced the number of matches from over 1000 down to 210:

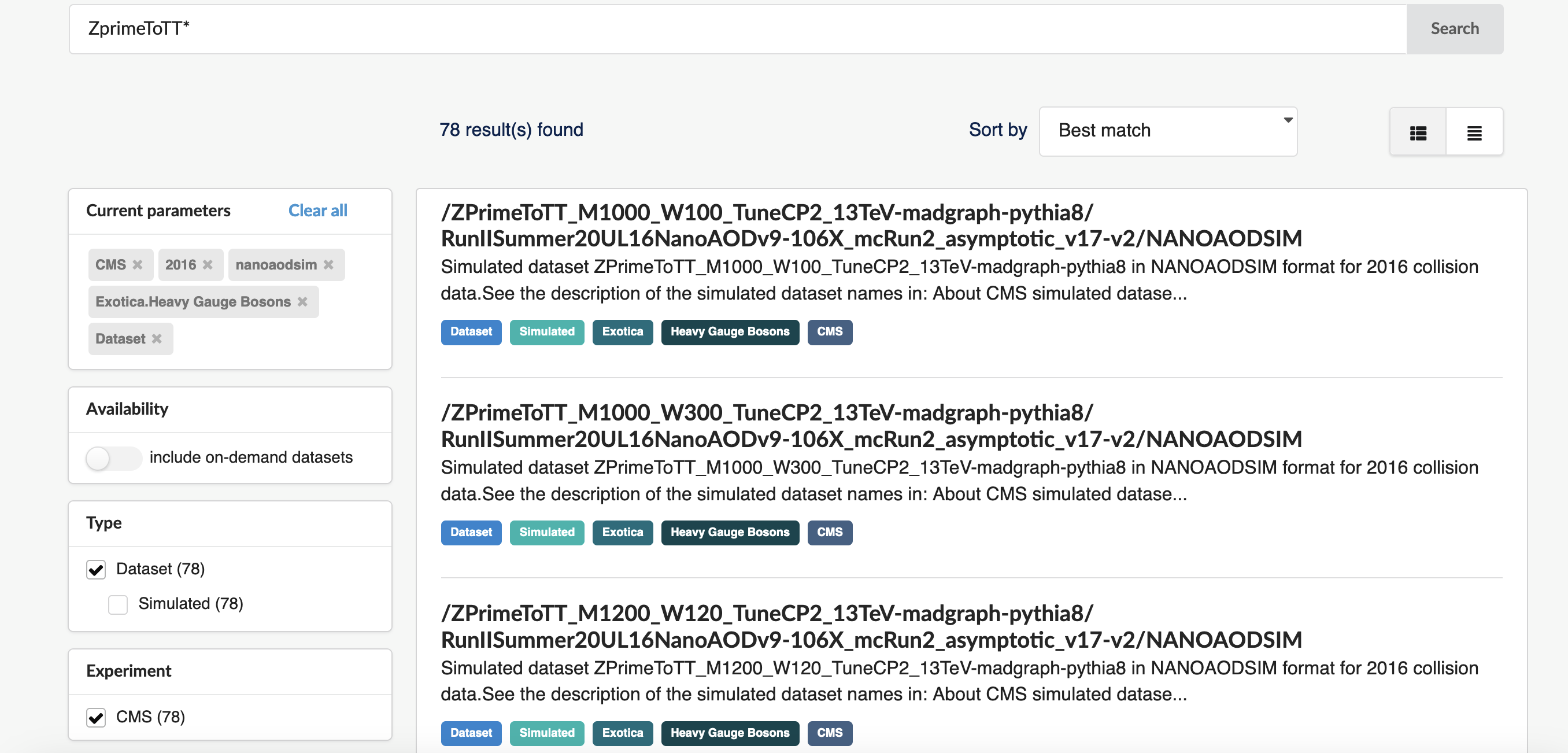

We can discern some of the logic behind the simulated dataset naming. “Zprime” is the particle produced and it decays to various products. We want \(Z^{'} \rightarrow t\bar{t}\) which shows up as the third result so let’s narrow the search further and search with “ZprimeToTT*“:

We can also discern that the dataset names also include the mass (in GeV) of the hypothetical Z’ (e.g. “_M2000”).

Why such long dataset names?

CMS open data are the same files that have been used in the data analysis by CMS members. The names come from naming conventions for the production system.

Go back to the pre-exercise for a brief explanation of the simulated dataset names.

Exercise 1: Select a Z’ mass and find the corresponding dataset

Search with “ZprimeToTT_M<mass>” where

<mass> is the value you selected.

Next, let’s use the cernopendata-client command-line

tool to find the datasets and fetch a file.

Exercise 2: Find a file name in the dataset

Go back to the pre-exercise to see how to get the file names with the command-line tool.

Explore a file

We will now have a look at the file contents.

How to know what variables are there?

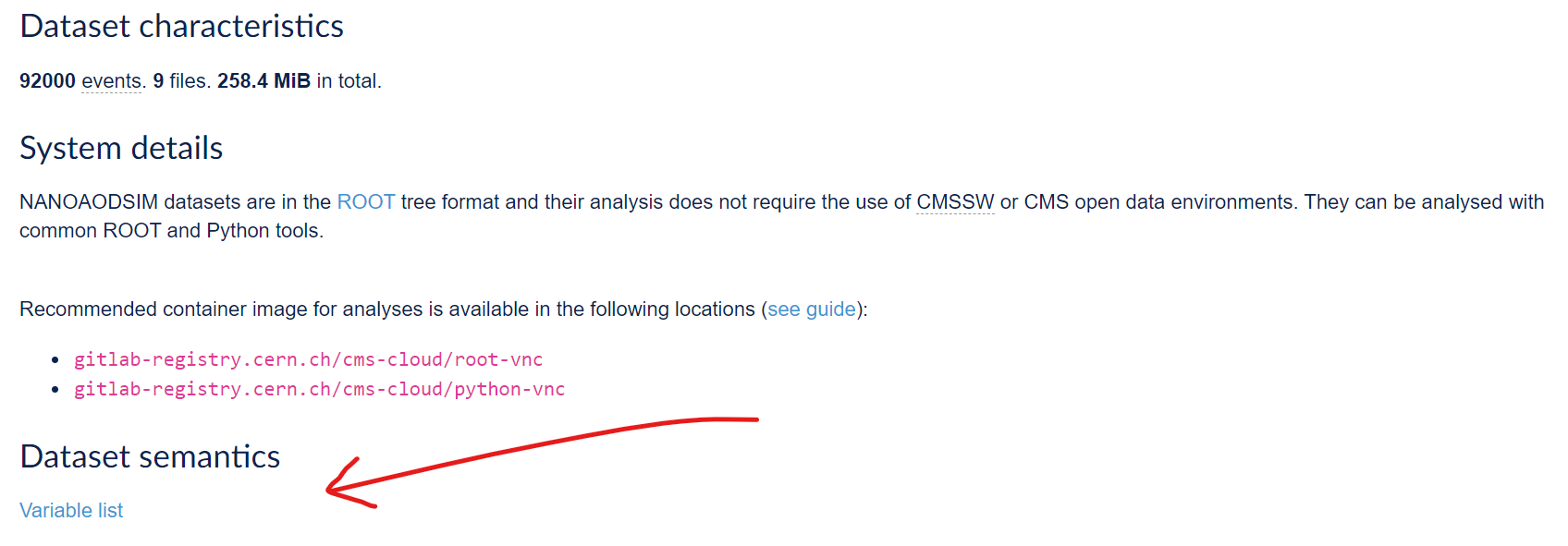

Remember that each NanoAOD/NanoAODSIM dataset has the variable list linked to the record:

And do not forget that the prelearning lesson on Physics Objects explains them in more detail!

Now let us plot the value of some these variables. Open the

my_python container

You can either write your code in a Python script, or use a jupyter notebook.

If you want to use jupyter notebooks, start jupyter-lab with

Open the link given in the message on your browser. Choose the icon under “Notebook”.

Exercise 3: Explore the file with the Python tools

Open the file and print the variable names.

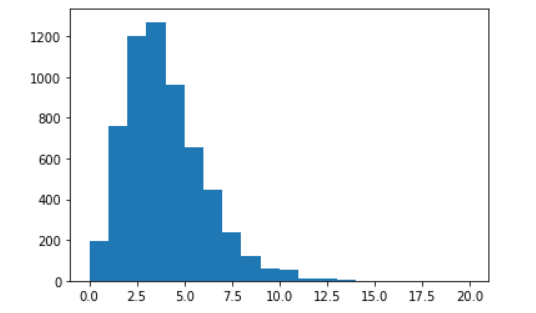

Make a plot of a variable that is a single number in an event, for example the number of secondary vertices.

Then plot some property of the selected variables, for example a property of the secondary vertices.

Go back to the pre-exercise to see how to open the file using uproot.

If you need exercising, try to do this without looking at the solutions!

First import the Python packages.

Open the file with uproot and inspect the first

layer.

Check what variables are available in Events.

Choose first a variable that is a single number in an event,

typically a number of certain objects in an event. You could take number

of muons, electrons or other particles, but let us take the number of

secondary vertices, nSV. They are points identified as

starting points of a track, different from the collision point, the

primary vertex. It is typically the decay point of some short-lived

particle. Make a histogram.

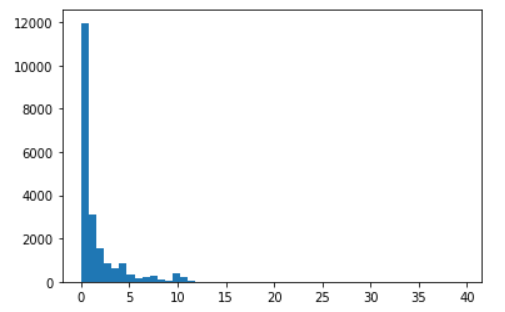

Then, choose a variable of a physics object that can be many in a

single event. You could take the pt values of electrons or muons, or if

we remain with the secondary vertices, take for example

SV_dxy, the 2D decay length in cm.

This is now a jagged array and to plot the values, you will

need to use the flatten() function from

awkward.

But first, inspect the array elements to see the multiple values per event

Print the number or secondary vertices per event (the value we just plotted):

Now, print the 2D decay lengths:

and some single elements of it so that you see that the lenght of corresponds to the number of secondary vertices:

Key Points

- Use search facets and text search with wildcards to narrow your search.

- You can find the variable names with a brief explanation from the record, explained more in detail in the prelearning lesson and print them out directly from the file.

- NanoAOD files can be opened using the

uprootpackage and theawkwardpackaged can be use to handle varying-length arrays.