Introduction

Last updated on 2024-07-09 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 5 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is the CMS detector?

- What are the design objectives of the CMS detector?

- What are the main detector components of the CMS detector?

Objectives

- Learn about the CMS detector and how it works.

Introduction and overview

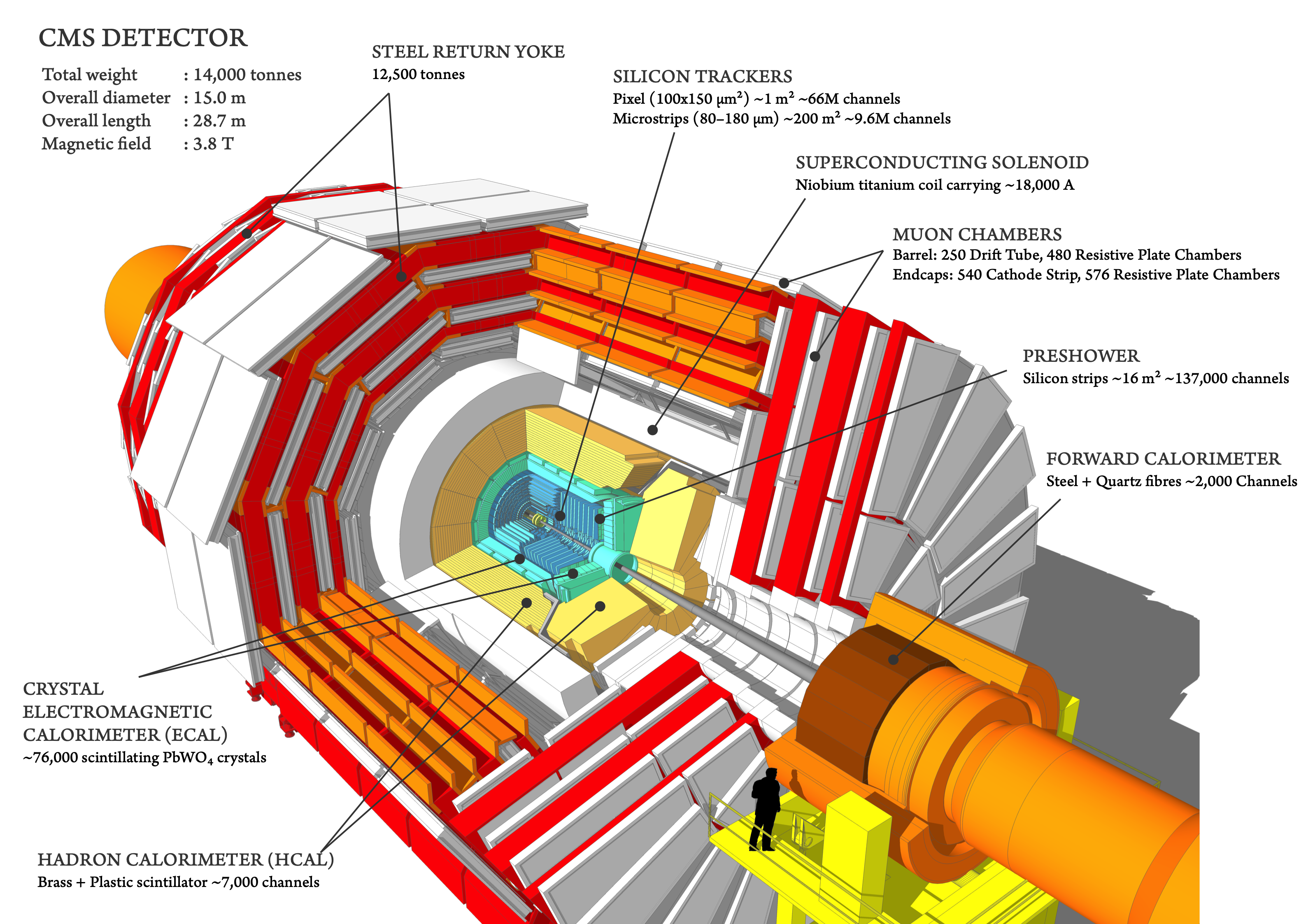

The CMS experiment is 21 m long, 15 m wide and 15 m high, and sits in a cavern that could contain all the residents of Geneva; albeit not comfortably. The detector is like a giant filter, where each layer is designed to stop, track or measure a different type of particle emerging from proton-proton and heavy ion collisions. Finding the energy and momentum of a particle gives clues to its identity, and particular patterns of particles or “signatures” are indications of new and exciting physics

Above: A schematic view of the CMS detector.

The detector is built around a huge solenoid magnet. This takes the form of a cylindrical coil of superconducting cable, cooled to -268.5oC, that generates a magnetic field of 4 Tesla, about 100,000 times that of the Earth.

Detectors consist of layers of material that exploit the different properties of particles to catch and measure the energy and momentum of each one. CMS needed:

- a high performance system to detect and measure muons,

- a high resolution method to detect and measure electrons and photons (an electromagnetic calorimeter),

- a high quality central tracking system to give accurate momentum measurements, and

- a “hermetic” hadron calorimeter, designed to entirely surround the collision and prevent particles from escaping.

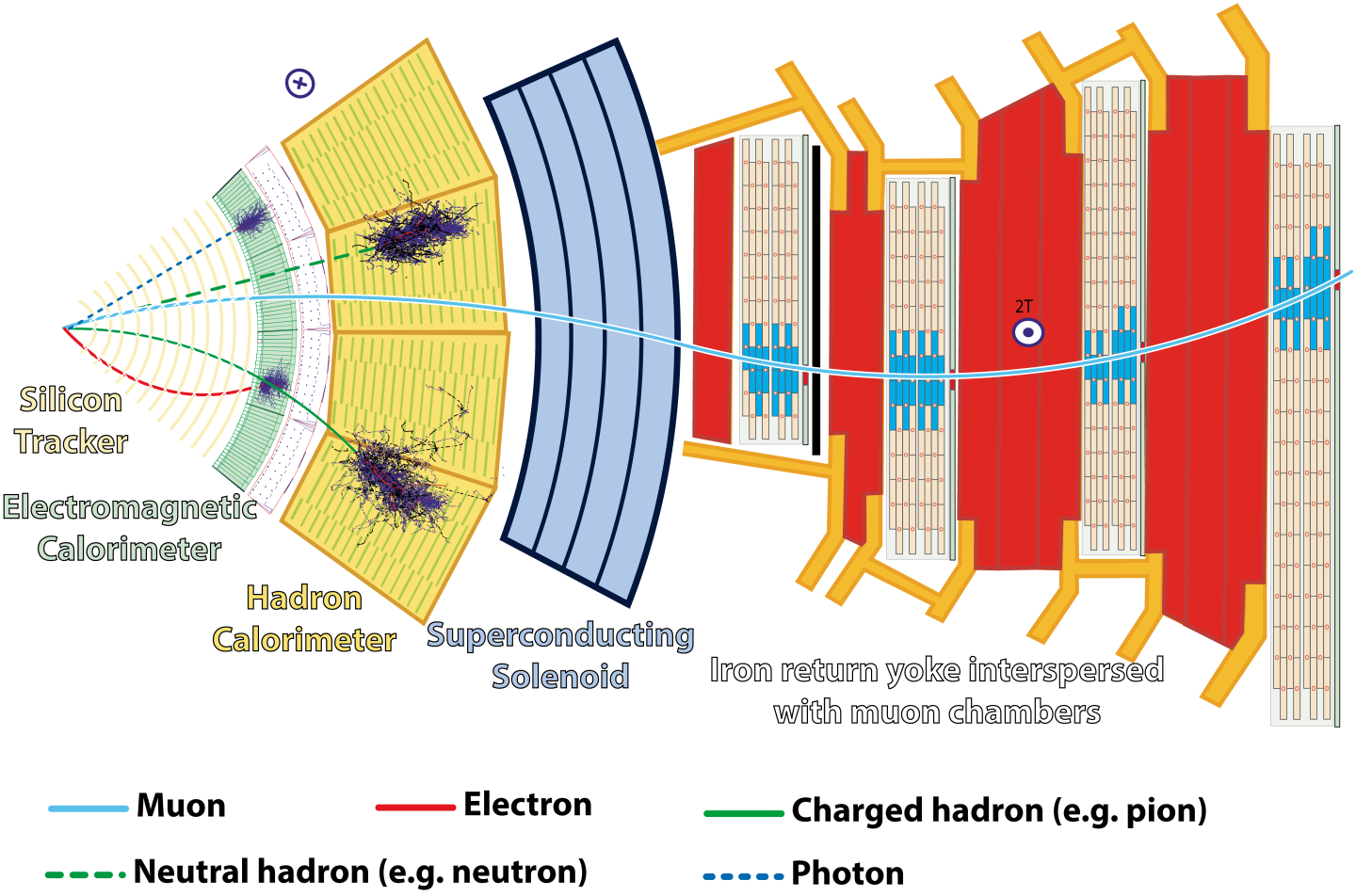

Particles emerging from collisions first meet a tracker, made entirely of silicon, that charts their positions as they move through the detector, allowing us to measure their momentum. Outside the tracker are calorimeters that measure the energy of particles. In measuring the momentum, the tracker should interfere with the particles as little as possible, whereas the calorimeters are specifically designed to stop the particles in their tracks.

The Electromagnetic Calorimeter (ECAL) - made of lead tungstate, a very dense material that produces light when hit – measures the energy of photons and electrons whereas the Hadron Calorimeter (HCAL) is designed principally to detect any particle made up of quarks (the basic building blocks of protons and neutrons). The size of the magnet allows the tracker and calorimeters to be placed inside its coil, resulting in an overall compact detector.

As the name indicates, CMS is also designed to measure muons. The outer part of the detector, the iron magnet “return yoke”, confines the magnetic field and stops all remaining particles except for muons and neutrinos. The muon tracks are measured by four layers of muon detectors that are interleaved with the iron yoke. The neutrinos escape from CMS undetected, although their presence can be indirectly inferred from the “missing transverse energy” in the event.

Within the LHC, bunches of particles collide up to 40 million times per second, so a “trigger” system that saves only potentially interesting events is essential. This reduces the number recorded from one billion to around 100 per second.

Below is an interactive 3D model of the CMS detector:

Key Points

- The CMS detector is a large general-purpose detector at the LHC, CERN.

- CMS consists of layers of detector material that exploit the different properties of particles to catch and measure the energy or momentum of each one.