Introduction

Overview

Teaching: 5 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What is C++?

What is ROOT?

What is the point of these exercises?

Objectives

Learn a bit about C++ and how to compile C++ code.

Learn how to use ROOT to write and read from files, using the C++ libraries.

learn how to use ROOT to investigate data and create simple histograms

Explore the ROOT python libraries.

Despite the order of the words in the title of this lesson, let’s talk about ROOT first!

What is ROOT?

From the ROOT website

ROOT is a framework for data processing, born at CERN, at the heart of the research on high-energy physics. Every day, thousands of physicists use ROOT applications to analyze their data or to perform simulations.

In short, ROOT is an overarching toolkit that defines a file structure, methods to analyze particle physics data, visualization tools, and is the backbone of many widely used statistical analysis tool kits, such as RooFit and RooStats. You don’t need to use ROOT for your own analysis, but you will have to have some familiarity with it when you are first accessing the open data.

OK, that sounds cool. So what’s the deal with C++?

ROOT and C++

In the mid-80’s, C++ extended the very popular C programming language, primarily with the introduction of object-oriented programming (OOP). This programming paradigm was adopted by many particle physics experiments in the 1990’s and when ROOT was written, it was written in C++. While there are now python hooks to call the ROOT functions, the underlying code is all in C++.

Because C++ is a compiled code, it is usually much faster than a scripted language like python, though that is changing with modern python tools. Still, since much of the original analysis and access code was written in C++ and calling the C++ ROOT libraries, it’s good to know some of the basics of ROOT, in a C++ context.

Most CMS analysts interface with ROOT using python scripts and you may find yourself using a similar workflow. Later on in this lesson, we’ll walk you through some very basic python scripts and point you toward more in-depth tutorials, for those who want to go further.

You still have choices!

Just to emphasize, you really only need to use ROOT and C++ at the very earliest stages of an analysis, when accessing the data and using some of the CMS-provided tools. However, downstream in your analysis, you are welcome to use whatever tools and file formats you choose.

Key Points

C++ has a reputation for being intimidating, but there are only a few things you need to learn to edit the open data code for your own uses.

You can use the ROOT toolkit using both C++ and python.

Some ROOT code is written in C++ to access the datafiles.

People will often use simpler C++ scripts or python scripts to analyze reduced datasets.

Lightning overview of C++

Overview

Teaching: 5 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How do I write and execute C++ code?

Objectives

To write a hello-world C++ program

Setting up your working area

If you completed the Docker pre-exercises you should already have worked through this episode, under Download the docker images for ROOT and python tools and start container, and you will have

- a working directory

cms_open_data_rooton your local computer - a docker container with name

my_rootcreated with the working directorycms_open_data_rootmounted into the/codedirectory of the container.

Start your ROOT container with

docker start -i my_root

In the container, you will be in the /code directory and it shares the files with your local cms_open_data_root directory.

Your first C/C++ program

Let’s start with writing a simple hello world program in C. First we’ll edit the

source code with an editor of your choice.

Note that you will

edit the file in a local terminal on your computer and then run the file

in the Docker environment. This is because we mounted the cms_open_data_root directory

on your local disk such that it is visible inside the Docker container.

Let’s create a new file called hello_world.cc in the cms_open_data_root directory, using your preferred editor.

The first thing we need to do, is include some standard libraries. These libraries

allow us to access the C and C++ commands to print to the screen (stdout and stderr) as

well as other basic function.

At the very beginning of your file, add these three lines

#include <cstdlib>

#include <cstdio>

#include <iostream>

The first library, cstdlib, you will see in almost every C++ program as it has many of the very

basic functions, including those to allocate and free up memory, or even just exit the program.

The second library, cstdio, contains the basic C functions to print to screen, like printf.

The third library, iostream, contains C++ functions to print to screen or write to files.

Usually people will use one or the other of the C or C++ printing functions, but for pedagogical purposes, we show you both.

Every C++ program must have a main function. So let’s define it here. The scope of this function

is defined by curly brackets { }. So let’s add

int main() {

return 0;

}

The int at the beginning tells us that this function will be returning an integer value. At the end of

the main function we have return 0, which usually means the function has run successfully to completion.

Warning!

Note that at the end of

return 0, we have a semicolon;, which is how C/C++ programs terminate lines. If you’re used to programming in python or any other language that does not use a similar terminator, this can be tough to remember. If you get errors when you compile, check the error statements for the lack of;in any of your lines!

For this function, we are not passing in any arguments so we just have the empty ( ) after the main.

This function would compile, but it doesn’t do anything. Let’s print some text to screen. Before

the return 0; line, let’s add these three lines.

printf("Hello world! This uses the ANSI C 'printf' statement\n");

std::cout << "Hello world! This uses the C++ 'iostream' library to direct output to standard out." << std::endl;

std::cerr << "Hello world! This uses the C++ 'iostream' library to direct output to standard error." << std::endl;

The text itself, should explain what they are doing. If you want to learn more about standard error and standard output, you can read more on Wikipedia.

OK! Your full hello_world.cc should look like this.

Full source code file for

hello_world.cc#include <cstdlib> #include <cstdio> #include <iostream> int main() { printf("Hello world! This uses the ANSI C 'printf' statement\n"); std::cout << "Hello world! This uses the C++ 'iostream' library to direct output to standard out." << std::endl; std::cerr << "Hello world! This uses the C++ 'iostream' library to direct output to standard error." << std::endl; return 0; }

This won’t do anything yet though! We need to compile the code, which means turning this into

machine code. To do this, we’ll use the GNU C++ compiler, g++.

Once you have saved your file, go to the container shell, make sure (e.g. with ls -l) that you your file is in the current directory and type this in your shell.

g++ hello_world.cc -o hello_world

This compiles your code to an executable called hello_world. You can now run this by typing the following on

the shell command line, after which you’ll see the subsequent output.

./hello_world

Hello world! This uses the ANSI C 'printf' statement

Hello world! This uses the C++ 'iostream' library to direct output to standard out.

Hello world! This uses the C++ 'iostream' library to direct output to standard error.

When you are working with the Open Data, you will be looping over events and may find yourself making selections based on certain physics criteria. To that end, you may want to familiarize yourself with the C++ syntax for loops and conditionals.

Key Points

We must compile our C++ code before we can execute it.

Using ROOT with C++ to write and read a file

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

Why do I need to use ROOT?

How do I use ROOT with C++?

Objectives

Write a ROOT file using compiled C++ code.

Read a ROOT file using compiled C++ code.

Why ROOT?

HEP data can be challenging! Not just to analyze but to store! The data don’t lend themselves to neat rows in a spreadsheet. One event might have 3 muons and the next event might have none. One event might have 2 jets and the next event might have 20. What to do???

The ROOT toolkit provides a file format that can allow for efficient storage of this type of data with heterogenous entries in each event. It also provides a pretty complete analysis environment with specialized libraries and visualization packages. Until recently, you had to install the entire ROOT package just to read a file. The software provided by CMS to read the open data relies on some minimal knowledge of ROOT to access. From there, you can write out more ROOT files for further analysis or dump the data (or some subset of the data) to a format of your choosing.

Interfacing with ROOT

ROOT is a toolkit. That is, it is a set of functions and libraries that can be utilized in a variety of languages and workflows. It was originally written in C++ and lends itself nicely to being used in standard, compiled C++ code.

However, analysts wanted something more interactive, and so the ROOT team developed

CINT, a C++ interpreter. This gave users

an iteractive environment where they could type of C++ code one line at a time and have it executed

immediately. This gave rise to C++ scripts that many analysts use and in fact the sample

ROOT tutorals

are almost exclusively written as these C++ scripts (with a .C file extension). Because they are written

to run in CINT, they usually do not need the standard C++ include statements that you will see

in the examples below.

With the rise of the popularity of python, a set of Python-C++ bindings were written and eventually officially supported by the ROOT development team, called PyROOT. Many analysts currently write the code which plots or fits their code using PyROOT, and we will show you some examples later in this exercise.

What won’t you learn here

ROOT is an incredibly powerful toolkit and has a lot in it. It is heavily used by most nuclear and particle physics experiments running today. As such, a full overview is beyond the scope of this minimal tutorial!

This tutorial will not teach you how to

- Make any plots more sophisticated than a basic histogram.

- Fit your data

- Use any of the HEP-specific libraries (e.g.

TLorentzVector)

OK, where can I learn that stuff?

There are some great resources and tutorials out there for going further.

- The official ROOT Primer. The recommended starting point to learn what ROOT can do.

- The official ROOT tutorials This is a fairly comprehensive listing of well-commented examples, written in C++ scripts that are designed to be run from within the ROOT C-interpreter.

- ROOT tutorial (2022).. Tutorial from offical ROOT project for summer students.

- Efficient analysis with ROOT. This is a more complete, end-to-end tutorial on using ROOT in a CMS analysis workflow. It was created in 2020 by some of our CMS colleagues for a separate workshop, but much of the material is relevant for the Open Data effort. It takes about 2.5 hours to complete the tutorial.

- ROOT tutorial from Nevis Lab (Columbia Univ.). Very complete and always up-to-date tutorial from our friends at Columbia.

Be in Docker!

For this episode, you’ll still be running your code from the

my_rootdocker container that you launched in the previous episode.As you edit the files though, you may want to do the editing from your local environment, so that you have access to your preferred editors.

ROOT terminology

To store these datasets, ROOT uses an object called TTree (ROOT objects are often prefixed by a T).

Each variable on the TTree, for example the transverse momentum of a muon, is stored in its own

TBranch.

Source code for C++ lessons

There’s a fair amount of C++ in this lesson and you’ll get the most out of it if you work through it all and type it all out.

However, it’s easy to make a mistake, particularly with the

Makefile. We’ve made the the source code available in this tarball. Just follow the link and click on the Download button or download it directly withwgetto you working directorycms_open_data_rootin your local bash terminal withwget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cms-opendata-workshop/workshop2022-lesson-cpp-root-python/gh-pages/data/root_and_cpp_tutorial_source_code.tgzUntar the file with

tar -zxvf root_and_cpp_tutorial_source_code.tgzIt will create a directory called

root_and_cpp_tutorial_source_codewith the files in it.

Write to a file

Let’s create a file with name write_ROOT_file.cc using our preferred editor. We’ll call this file write_ROOT_file.cc and it will be saved in the cms_open_data_root directory.

As in our last example, we first include some header files, both the standard C++ ones

and some new ROOT-specific ones.

#include <cstdio>

#include <cstdlib>

#include <iostream>

#include "TROOT.h"

#include "TTree.h"

#include "TFile.h"

#include "TRandom.h"

Note the inclusion of TRandom.h, which we’ll be using to generate some random data for our

test file.

Next, we’ll create our main function and start it off by defining our ROOT

file object. We’ll also include some explanatory comments, which in the C++ syntax

are preceded by two slashes, //.

int main() {

// Create a ROOT file, f.

// The first argument, "tree.root" is the name of the file.

// The second argument, "recreate", will recreate the file, even if it already exists.

TFile f("tree.root","recreate");

return 0;

}

Now we define the TTree object which will hold all of our variables and the data they represent.

This line comes after the TFile creation, but before the return 0 statement at the end of the

main function. Subsequent edits will also follow the previous edit but come before return 0 statement.

// A TTree object called t1.

// The first argument is the name of the object as stored by ROOT.

// The second argument is a short descriptor.

TTree t1("t1","A simple Tree with simple variables");

For this example, we’ll assume we’re recording the missing transverse energy, which means there is only one value recorded for each event.

We’ll also record the energy and momentum (transverse momentum, eta, phi) for jets, where there could be between 0 and 5 jets in each event.

This means we will define some C++ variables that will be used in the program.

We do this before we define the TBranches in the TTree.

When we define the variables, we use ROOT’s Float_t and Int_t types, which

are analogous to float and int but are less dependent on the underlying

computer OS and architecture.

Float_t met; // Missing energy in the transverse direction.

Int_t njets; // Necessary to keep track of the number of jets

// We'll define these assuming we will not write information for

// more than 16 jets. We'll have to check for this in the code otherwise

// it could crash!

Float_t pt[16];

Float_t eta[16];

Float_t phi[16];

We now define the TBranch for the met variable.

// The first argument is ROOT's internal name of the variable.

// The second argument is the *address* of the actual variable we defined above

// The third argument defines the *type* of the variable to be stored, and the "F"

// at the end signifies that this is a float

t1.Branch("met",&met,"met/F");

Next we define the TBranches for each of the other variables, but the syntax is slightly different

as these are acting as arrays with a varying number of entries for each event.

// First we define njets where the syntax is the same as before,

// except we take care to identify this as an integer with the final

// /I designation

t1.Branch("njets",&njets,"njets/I");

// We can now define the other variables, but we use a slightly different

// syntax for the third argument to identify the variable that will be used

// to count the number of entries per event

t1.Branch("pt",&pt,"pt[njets]/F");

t1.Branch("eta",&eta,"eta[njets]/F");

t1.Branch("phi",&phi,"phi[njets]/F");

OK, we’ve defined where everything will be stored! Let’s now generate 1000 mock events.

Int_t nevents = 1000;

for (Int_t i=0;i<nevents;i++) {

// Generate random number between 10-60 (arbitrary)

met = 50*gRandom->Rndm() + 10;

// Generate random number between 0-5, inclusive

njets = gRandom->Integer(6);

for (Int_t j=0;j<njets;j++) {

pt[j] = 100*gRandom->Rndm();

eta[j] = 6*gRandom->Rndm();

phi[j] = 6.28*gRandom->Rndm() - 3.14;

}

// After each event we need to *fill* the TTree

t1.Fill();

}

// After we've run over all the events, we "change directory" (cd) to the file object

// and write the tree to it.

// We can also print the tree, just as a visual identifier to ourselves that

// the program ran to completion.

f.cd();

t1.Write();

t1.Print();

The full write_ROOT_file.cc should now look like this

Full source code file for

write_ROOT_file.cc#include <cstdio> #include <cstdlib> #include <iostream> #include "TROOT.h" #include "TTree.h" #include "TFile.h" #include "TRandom.h" int main() { // Create a ROOT file, f. // The first argument, "tree.root" is the name of the file. // The second argument, "recreate", will recreate the file, even if it already exists. TFile f("tree.root", "recreate"); // A TTree object called t1. // The first argument is the name of the object as stored by ROOT. // The second argument is a short descriptor. TTree t1("t1", "A simple Tree with simple variables"); Float_t met; // Missing energy in the transverse direction. Int_t njets; // Necessary to keep track of the number of jets // We'll define these assuming we will not write information for // more than 16 jets. We'll have to check for this in the code otherwise // it could crash! Float_t pt[16]; Float_t eta[16]; Float_t phi[16]; // The first argument is ROOT's internal name of the variable. // The second argument is the *address* of the actual variable we defined above // The third argument defines the *type* of the variable to be stored, and the "F" // at the end signifies that this is a float t1.Branch("met",&met,"met/F"); // First we define njets where the syntax is the same as before, // except we take care to identify this as an integer with the final // /I designation t1.Branch("njets", &njets, "njets/I"); // We can now define the other variables, but we use a slightly different // syntax for the third argument to identify the variable that will be used // to count the number of entries per event t1.Branch("pt", &pt, "pt[njets]/F"); t1.Branch("eta", &eta, "eta[njets]/F"); t1.Branch("phi", &phi, "phi[njets]/F"); Int_t nevents = 1000; for (Int_t i=0;i<nevents;i++) { // Generate random number between 10-60 (arbitrary) met = 50*gRandom->Rndm() + 10; // Generate random number between 0-5, inclusive njets = gRandom->Integer(6); for (Int_t j=0;j<njets;j++) { pt[j] = 100*gRandom->Rndm(); eta[j] = 6*gRandom->Rndm(); phi[j] = 6.28*gRandom->Rndm() - 3.14; } // After each event we need to *fill* the TTree t1.Fill(); } // After we've run over all the events, we "change directory" to the file object // and write the tree to it. // We can also print the tree, just as a visual identifier to ourselves that // the program ran to completion. f.cd(); t1.Write(); t1.Print(); return 0; }

Because we need to compile this in such a way that it links to the ROOT libraries, we will use a Makefile

to simplify the build process.

Create a new file called Makefile in the same directory as write_ROOT_file.cc and add the following to the

file. You’ll most likely do this with the editor of your choice.

CC=g++

CFLAGS=-c -g -Wall `root-config --cflags`

LDFLAGS=`root-config --glibs`

all: write_ROOT_file

write_ROOT_file: write_ROOT_file.cc

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -o write_ROOT_file.o write_ROOT_file.cc

$(CC) -o write_ROOT_file write_ROOT_file.o $(LDFLAGS)

Warning! Tabs are important in Makefiles!

Makefiles have been around a long time and are used for many projects, not just C/C++ code. While other build tools are slowly supplanting them (e.g. CMake), Makefiles are a pretty tried and true standard and it is worth taking time at some point and learning more about them.

One frustrating thing though can be a Makefile’s reliance on tabs for specific purposes. In the example above, the following lines are preceeded by a tab and not four (4) spaces.

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -o write_ROOT_file.o write_ROOT_file.cc $(CC) -o write_ROOT_file write_ROOT_file.o $(LDFLAGS)If your Makefile has spaces at those points instead of a tab,

makewill not work for you and you will get an error.

You can now compile and run your compiled program from the command line of your my_root container shell!

make write_ROOT_file

./write_ROOT_file

Output from

write_ROOT_file****************************************************************************** *Tree :t1 : A simple Tree with simple variables * *Entries : 1000 : Total = 51536 bytes File Size = 36858 * * : : Tree compression factor = 1.35 * ****************************************************************************** *Br 0 :met : met/F * *Entries : 1000 : Total Size= 4542 bytes File Size = 3641 * *Baskets : 1 : Basket Size= 32000 bytes Compression= 1.12 * *............................................................................* *Br 1 :njets : njets/I * *Entries : 1000 : Total Size= 4552 bytes File Size = 841 * *Baskets : 1 : Basket Size= 32000 bytes Compression= 4.84 * *............................................................................* *Br 2 :pt : pt[njets]/F * *Entries : 1000 : Total Size= 14084 bytes File Size = 10445 * *Baskets : 1 : Basket Size= 32000 bytes Compression= 1.29 * *............................................................................* *Br 3 :eta : eta[njets]/F * *Entries : 1000 : Total Size= 14089 bytes File Size = 10424 * *Baskets : 1 : Basket Size= 32000 bytes Compression= 1.30 * *............................................................................* *Br 4 :phi : phi[njets]/F * *Entries : 1000 : Total Size= 14089 bytes File Size = 10758 * *Baskets : 1 : Basket Size= 32000 bytes Compression= 1.26 * *............................................................................*

Your numbers may be slightly different because of the random numbers that are generated.

After you’ve run this, you can look in this directory (ls -ltr) and see

if you have a new file called tree.root. This is the output

of what you just ran.

Huzzah! You’ve successfully written your first ROOT file!

Will I have to

makemy Open Data analysis code?Yes, you will! However, you won’t actually call

make, nor will you need to write your ownMakefile. Instead, the CMS software uses a configuration and build system called SCRAM.So instead of typing

make, you’ll find yourself typingscram. However, it serves the same purpose by compiling and linking your code for you.

Read a ROOT file

Let’s try to read the tree.root file now. We won’t do much with but we’ll try to understand the process necessary

to read in all the data and loop over this event-by-event.

You will now edit (with your favourite editor) a file called read_ROOT_file.cc. In this file,

you’ll add the following code.

We’ll start with the basic include statements and the main program.

#include <cstdio>

#include <cstdlib>

#include <iostream>

#include "TROOT.h"

#include "TTree.h"

#include "TFile.h"

#include "TRandom.h"

int main() {

return 0;

}

In the main function, we’ll define the input file.

// Here's the input file

// Without the 'recreate' argument, ROOT will assume this file exists to be read in.

TFile f("tree.root");

We’ll make use of the built-in member functions to TFile to pull out the TTree named

t1. There’s a few other things to note.

First, we’re going to assign it to a local variable named input_tree. This is to emphasize

that t1 is just a string that refers to the name of the object stored in the TFile and

that we can assign it to any variable name, not just one named t1.

The second thing to note is that we are going to create a pointer to input_tree, which makes

some of the memory management easier. This means that we precede our variable name with

an asterix *, we have to cast the object pulled out of the TFile as a TTree pointer (TTree*),

and subsequent uses of input_tree will access data members and member functions with

the -> operator rather than a period ..

If you want to learn more about pointers, there are many, many, resources out there.

// We will now "Get" the tree from the file and assign it to

// a new local variable.

TTree *input_tree = (TTree*)f.Get("t1");

Just as we did in the write_ROOT_file.cc example, we will define some local variables.

These variables will actually get “filled” by the ROOT file when we loop over the events.

Float_t met;

Int_t njets;

Float_t pt[16];

Float_t eta[16];

Float_t phi[16];

We’ll now assign these local variables to specific TBranches in input_tree. Note

that we’ll be using the address of each local variable when we precede

the variable name with an ampersand &.

// Assign these variables to specific branch addresses

input_tree->SetBranchAddress("met", &met);

input_tree->SetBranchAddress("njets", &njets);

input_tree->SetBranchAddress("pt", &pt);

input_tree->SetBranchAddress("eta", &eta);

input_tree->SetBranchAddress("phi", &phi);

We’re ready now to loop over events! Each time we call input_tree->GetEntry(i),

it pulls the ith values out of input_tree and “fills” the local variables

with those values.

for (Int_t i=0;i<nevents;i++) {

// Get the values for the i`th event and fill all our local variables

// that were assigned to TBranches

input_tree->GetEntry(i);

// Print the number of jets in this event

printf("%d\n", njets);

// Print out the momentum for each jet in this event

for (Int_t j=0; j<njets; j++) {

printf("%f, %f, %f\n", pt[j], eta[j], phi[j]);

}

}

The final version of your read_ROOT_file.cc should look like

Full source code file for

read_ROOT_file.cc#include <cstdio> #include <cstdlib> #include <iostream> #include "TROOT.h" #include "TTree.h" #include "TFile.h" #include "TRandom.h" int main() { // Here's the input file // Without the 'recreate' argument, ROOT will assume this file exists to be read in. TFile f("tree.root"); // We will now "Get" the tree from the file and assign it to // a new local variable. TTree *input_tree = (TTree*)f.Get("t1"); Float_t met; // Missing energy in the transverse direction. Int_t njets; // Necessary to keep track of the number of jets // We'll define these assuming we will not write information for // more than 16 jets. We'll have to check for this in the code otherwise // it could crash! Float_t pt[16]; Float_t eta[16]; Float_t phi[16]; // Assign these variables to specific branch addresses input_tree->SetBranchAddress("met", &met); input_tree->SetBranchAddress("njets", &njets); input_tree->SetBranchAddress("pt", &pt); input_tree->SetBranchAddress("eta", &eta); input_tree->SetBranchAddress("phi", &phi); // Get the number of events in the file Int_t nevents = input_tree->GetEntries(); for (Int_t i=0;i<nevents;i++) { // Get the values for the i`th event and fill all our local variables // that were assigned to TBranches input_tree->GetEntry(i); // Print the number of jets in this event printf("%d\n",njets); // Print out the momentum for each jet in this event for (Int_t j=0; j<njets; j++) { printf("%f, %f, %f\n", pt[j], eta[j], phi[j]); } } return 0; }

Now we need to modify our Makefile to compile this code.

We edit it so that it looks like this.

CC=g++

CFLAGS=-c -g -Wall `root-config --cflags`

LDFLAGS=`root-config --glibs`

all: write_ROOT_file read_ROOT_file

write_ROOT_file: write_ROOT_file.cc

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -o write_ROOT_file.o write_ROOT_file.cc

$(CC) -o write_ROOT_file write_ROOT_file.o $(LDFLAGS)

read_ROOT_file: read_ROOT_file.cc

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -o read_ROOT_file.o read_ROOT_file.cc

$(CC) -o read_ROOT_file read_ROOT_file.o $(LDFLAGS)

clean:

rm -f ./*~ ./*.o ./write_ROOT_file

rm -f ./*~ ./*.o ./read_ROOT_file

We can now compile and run the code in your my_root container shell!

make read_ROOT_file

./read_ROOT_file

We get a lot of output! However it should look something like the following, keeping in mind your numbers will be different because of the random numbers that make up the values.

Output of

read_ROOT_file1 85.105431, 5.602912, 0.501085 1 18.954712, 4.375443, -1.546321 1 39.784435, 5.165263, 2.592412 3 80.748314, 0.387768, 1.786288 52.971573, 3.939434, 2.484405 12.969198, 3.115963, 0.910543 3 93.604256, 0.737315, -0.647755 86.382034, 3.493269, -1.573663 68.181541, 3.658454, -1.206015 3 96.990395, 5.839735, 3.046098 79.096542, 4.515290, 0.039709 83.234497, 4.990829, 2.586360 4 60.880657, 1.233623, -2.837789 25.723198, 4.751074, 2.355202 20.403908, 4.656353, -2.171340 18.961079, 1.425917, 2.016828

Awesome! You’ve now written and read in a very simple ROOT file! There is obviously much more

that can be done, but this should give you the basics of interfacing with ROOT TFiles and

TTrees.

You’ll see some version of this code when using analyzers to run over the open data code. At that point, you can write out subsets of the data to new ROOT files or even simply dump the data to a text or .csv file.

In the next section, we’ll take a quick look at how to read in a file and make a few histograms, still using the C++ syntax.

Key Points

ROOT defines the file format in which all of the CMS Open Data is stored.

These files can be accessed quickly using C++ code and the relevant information can be dumped out into other formats.

Using ROOT with C++ to fill a histogram

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

Is there more than reading and writing files that can be done with ROOT?

How do I run a ROOT script?

Objectives

Learn to fill a histogram and save it to a file.

Learn to run a simple ROOT script

Filling a histogram

ROOT can easily fill a histogram as you are looping over individual events. Let’s

try creating and filling a histogram with the transverse momentum values. We’ll start

with the read_ROOT_file.cc code we wrote in the previous episode and copy what

we have to a new file, fill_histogram.cc.

cp read_ROOT_file.cc fill_histogram.cc

Into this file, we’ll add some lines at some key spots. Again, use your favourite editor on your local computer. For now, we’ll go through those lines of code individually, and then show you the completed file at the end to see where they went.

First we need to include the header file for the ROOT TH1F class.

#include "TH1F.h"

We create an output file to store the histogram in.

// Let's make an output file which we'll use to save our

// histogram

TFile fout("output.root","recreate");

Define the histogram.

// We define an histogram for the transverse momentum of the jets

// The arguments are as follow

// * Internal name of the histogram

// * Title that will be used if the histogram is plotted

// * Number of bins

// * Low edge of the lowest bin

// * High edge of the highest bin

TH1F h1("h1","jet pT (GeV/c)",50,0,150);

And then inside the event loop, we fill the histogram each time we get a new value for the transverse momentum.

// Fill the histogram with each value of pT

h1.Fill(pt[j]);

Before we leave the function, we “change directory” to the output file, write the histogram to the file, and then close the output file.

fout.cd();

h1.Write();

fout.Close();

The final version of fill_histogram.cc will look like this.

Source code for

fill_histogram.cc#include<cstdio> #include<cstdlib> #include<iostream> #include "TROOT.h" #include "TTree.h" #include "TFile.h" #include "TRandom.h" #include "TH1F.h" int main() { // Here's the input file // Without the 'recreate' argument, ROOT will assume this file exists to be read in. TFile f("tree.root"); // Let's make an output file which we'll use to save our // histogram TFile fout("output.root","recreate"); // We define an histogram for the transverse momentum of the jets // The arguments are as follow // * Internal name of the histogram // * Title that will be used if the histogram is plotted // * Number of bins // * Low edge of the lowest bin // * High edge of the highest bin TH1F h1("h1","jet pT (GeV/c)",50,0,150); // We will now "Get" the tree from the file and assign it to // a new local variable. TTree *input_tree = (TTree*)f.Get("t1"); Float_t met; // Missing energy in the transverse direction. Int_t njets; // Necessary to keep track of the number of jets // We'll define these assuming we will not write information for // more than 16 jets. We'll have to check for this in the code otherwise // it could crash! Float_t pt[16]; Float_t eta[16]; Float_t phi[16]; // Assign these variables to specific branch addresses input_tree->SetBranchAddress("met",&met); input_tree->SetBranchAddress("njets",&njets); input_tree->SetBranchAddress("pt",&pt); input_tree->SetBranchAddress("eta",&eta); input_tree->SetBranchAddress("phi",&phi); // Get the number of events in the file Int_t nevents = input_tree->GetEntries(); for (Int_t i=0;i<nevents;i++) { // Get the values for the i`th event and fill all our local variables // that were assigned to TBranches input_tree->GetEntry(i); // Print the number of jets in this event printf("%d\n",njets); // Print out the momentum for each jet in this event for (Int_t j=0;j<njets;j++) { printf("%f,%f,%f\n",pt[j], eta[j], phi[j]); // Fill the histogram with each value of pT h1.Fill(pt[j]); } } fout.cd(); h1.Write(); fout.Close(); return 0; }

We will modify our Makefile accordingly.

CC=g++

CFLAGS=-c -g -Wall `root-config --cflags`

LDFLAGS=`root-config --glibs`

all: write_ROOT_file read_ROOT_file fill_histogram

write_ROOT_file: write_ROOT_file.cc

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -o write_ROOT_file.o write_ROOT_file.cc

$(CC) -o write_ROOT_file write_ROOT_file.o $(LDFLAGS)

read_ROOT_file: read_ROOT_file.cc

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -o read_ROOT_file.o read_ROOT_file.cc

$(CC) -o read_ROOT_file read_ROOT_file.o $(LDFLAGS)

fill_histogram: fill_histogram.cc

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -o fill_histogram.o fill_histogram.cc

$(CC) -o fill_histogram fill_histogram.o $(LDFLAGS)

clean:

rm -f ./*~ ./*.o ./write_ROOT_file

rm -f ./*~ ./*.o ./read_ROOT_file

rm -f ./*~ ./*.o ./fill_histogram

And then compile and run it, remember to do it in the container!

make fill_histogram

./fill_histogram

The output on the screen should not look different. However, if you list the contents of the directory,

you’ll see a new file, output.root!

If you are using a container with VNC, now it is time to start the graphics window with

start_vnc

and connect to it with the default password cms.cern.

To inspect this new ROOT file, we’ll launch CINT for the first time and create a

TBrowser object.

On the command line, run the following to launch CINT and attach our new ROOT file.

root -l output.root

root [0]

Attaching file output.root as _file0...

root [1]

You can either type C++/ROOT commands or launch a TBrowser, which is a graphical tool

to inspect ROOT files. Inside this CINT environment, type the following

(without the root [1], as that is just the ROOT/CINT prompt).

root [1] TBrowser b;

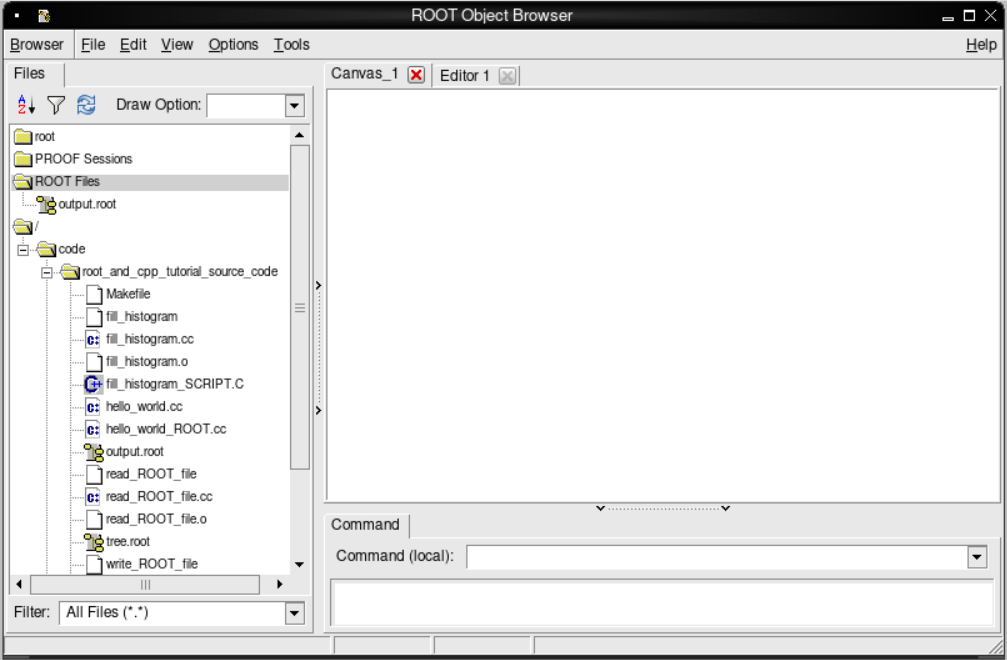

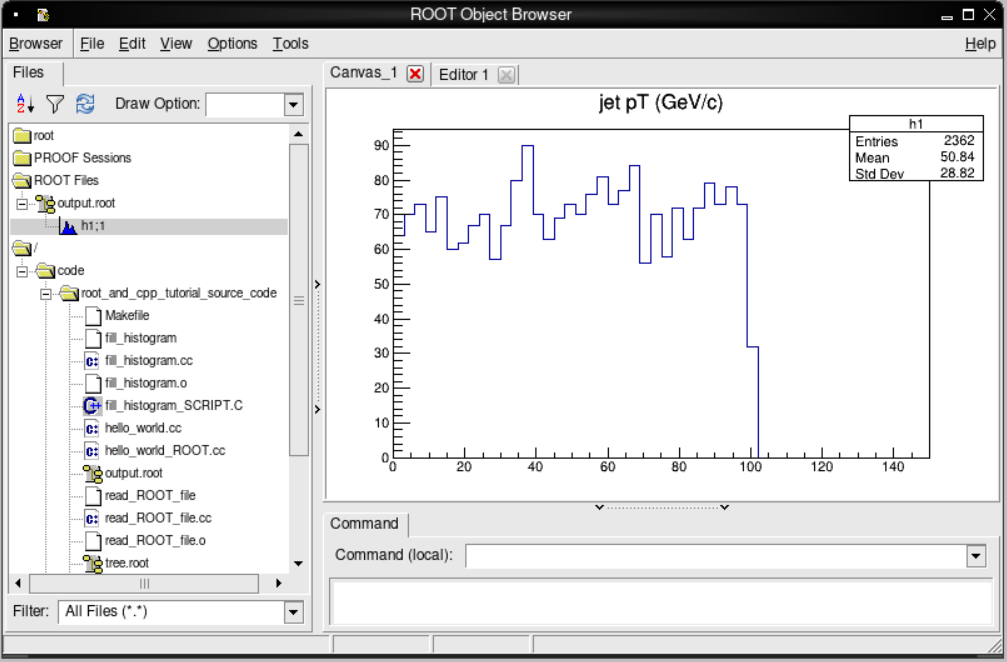

You should see the TBrowser pop up!

TBrowser

If we double click on output.root, in the left-hand menu and then the h1;1 that appears below it, we

should see the following plot appear!

Inspecting the ROOT file contents

Quit ROOT by choosing the “Quit Root” option from Browser menu of the TBrowser window or by typing .q in the ROOT prompt.

Work assignment: investigating data in ROOT files

In the previous episode you generated a file called

tree.root. It has some variables which were stored in a TTree calledt1. Let’s explore the variables contained in this tree by using one of the methods available for TTree objects. You can find out more about these methods directly from the ROOT TTree class documentation.Open the

tree.rootfile with ROOT:root -l tree.rootNow, dump the content of the

t1tree with the methodroot [0] Attaching file tree.root as _file0... root [1] t1->Print()Please copy the output this statement generates and paste it into the corresponding section in our assignment form; remember you must sign in and click on the submit button in order to save your work. You can go back to edit the form at any time. Then, quit ROOT.

Using a ROOT script

We could also loop over all the events, create and save the histogram, but also

draw the histogram onto a TCanvas object and have it pop up, all from a ROOT

script and the CINT.

First, let’s copy over our C++ source code into a C++ script.

cp fill_histogram.cc fill_histogram_SCRIPT.C

Next we’ll remove the headers at the beginning and even get rid of the int main designation,

though we keep the curly brackets.

We’ll also define a TCanvas object on which we’ll plot our histogram. After we do that,

we “change directory” to the canvas and draw our histogram. We can even save it to a

.png file.

// Declare a TCanvas with the following arguments

// * Internal name of the TCanvas object

// * Title to be displayed when it is drawn

// * Width of the canvas

// * Height of the canvas

TCanvas *c1 = new TCanvas("c1", "Canvas on which to display our histogram", 800, 400);

c1->cd(0);

h1.Draw();

c1->SaveAs("h_pt.png");

Your fill_histogram_SCRIPT.C should look like this.

Source code for

fill_histogram_SCRIPT.C{ // Here's the input file // Without the 'recreate' argument, ROOT will assume this file exists to be read in. TFile f("tree.root"); // Let's make an output file which we'll use to save our // histogram TFile fout("output.root","recreate"); // We define an histogram for the transverse momentum of the jets // The arguments are as follow // * Internal name of the histogram // * Title that will be used if the histogram is plotted // * Number of bins // * Low edge of the lowest bin // * High edge of the highest bin TH1F h1("h1","jet pT (GeV/c)",50,0,150); // We will now "Get" the tree from the file and assign it to // a new local variable. TTree *input_tree = (TTree*)f.Get("t1"); Float_t met; // Missing energy in the transverse direction. Int_t njets; // Necessary to keep track of the number of jets // We'll define these assuming we will not write information for // more than 16 jets. We'll have to check for this in the code otherwise // it could crash! Float_t pt[16]; Float_t eta[16]; Float_t phi[16]; // Assign these variables to specific branch addresses input_tree->SetBranchAddress("met",&met); input_tree->SetBranchAddress("njets",&njets); input_tree->SetBranchAddress("pt",&pt); input_tree->SetBranchAddress("eta",&eta); input_tree->SetBranchAddress("phi",&phi); // Get the number of events in the file Int_t nevents = input_tree->GetEntries(); for (Int_t i=0;i<nevents;i++) { // Get the values for the i`th event and fill all our local variables // that were assigned to TBranches input_tree->GetEntry(i); // Print the number of jets in this event printf("%d\n",njets); // Print out the momentum for each jet in this event for (Int_t j=0;j<njets;j++) { printf("%f,%f,%f\n",pt[j], eta[j], phi[j]); // Fill the histogram with each value of pT h1.Fill(pt[j]); } } // Declare a TCanvas with the following arguments // * Internal name of the TCanvas object // * Title to be displayed when it is drawn // * Width of the canvas // * Height of the canvas TCanvas *c1 = new TCanvas("c1", "Canvas on which to display our histogram", 800, 400); c1->cd(0); h1.Draw(); c1->SaveAs("h_pt.png"); fout.cd(); h1.Write(); fout.Close(); }

To run this, you need only type the following on the command line.

root -l fill_histogram_SCRIPT.C

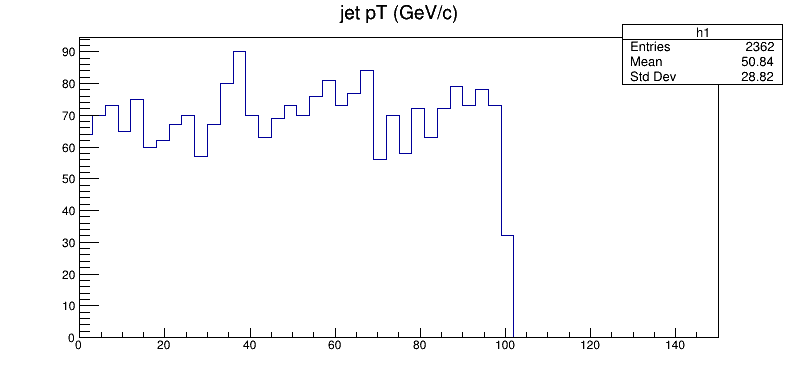

You’ll be popped into the CINT environment and you should see the following plot pop up!

TBrowser

Exit from the container. If you are using a container with VNC, first stop VNC with stop_vnc.

Key Points

You can quickly inspect your data using just ROOT

A simple ROOT script is often all you need for diagnostic work

Using ROOT with python

Overview

Teaching: 0 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

Can I call ROOT from python?

Objectives

Find resources

PyROOT

The PyROOT project started with Wim Lavrijsen in the late `00s and became very popular, paralleling the rise of more general python tools within the community.

If you want to learn how to use PyROOT, you can go through some individual examples here, or a more guided tutorial here.

Feel free to challenge yourself to rewrite the previous C++ code using PyROOT!

Key Points

PyROOT is a complete interface to the ROOT libraries

Installing python and the analysis tools locally

Overview

Teaching: 5 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How do I set up my local python environment?

How do I install uproot and awkward?

Objectives

Prepare your laptop or deskop computer to use python 3.x

Install some standard libraries, including uproot and awkward

Python has become the primary analysis language for the majority of HEP experimentalists. It has a rich ecosystem that is constantly evolving. This is a good thing because it means that improvements and new tools are always being developed, but it can sometimes be a challenge to keep up with the latest and greatest projects! :)

In this section, we will set up an environment in which you can explore some more modern python tools. We’ll show you two approaches:

- Make use of a Docker container (recommended)

- Install a local python environment on your laptop

In either case, these tools will allow you to can easily open and analyze ROOT files. This is useful for when you make use of the CMS open data tools to skim some subset of the open data and then copy it to your local laptop, desktop, or perhaps an HPC cluster at your home institution.

Option 1: Making use of Docker

If you would rather not install python from Anaconda, or keep your existing python tools separate from the CMS open data work, you can use the python Docker container. If you completed the Docker pre-exercises you should already have worked through this episode, under Download the docker images for ROOT and python tools and start container, and you will have

- a working directory

cms_open_data_pythonon your local computer - a docker container with name

my_pythoncreated with the working directorycms_open_data_pythonmounted into the/codedirectory of the container.

Start your python container with

docker start -i my_python

In the container, you will be in the /code directory and it shares the files with your local cms_open_data_python directory.

If you want to test out the installation, from within Docker you can launch and

interactive python session by typing python (in Docker) and then trying

import uproot

import awkward as ak

If you don’t get any errors then congratulations! You have a working environment and you are ready to perform some HEP analysis with your new python environment!

Option 2: Installing python with Anaconda

We recommend working with a newer python release, preferably python 3.7 or higher. Even if you have a standard python installation (as comes with many Mac computers), we recommend installing the popular (and free) Anaconda python distribution. This will give you an easily extendible python ecosystem. To install it for Windows, Mac, or Linux, head to

https://www.anaconda.com/products/distribution

Follow the instructions to install the Anaconda version of python and make it your default version. You’ll need between to 600 MB to 1 GB free disk space and depending on the speed of your connection, it can take up to 15 minutes to download.

Install the extra packages

We now want to install some additional python libraries.

- numpy, a very useful library to do fast, efficient manipulations of arrays of numbers.

- matplotlib, for most people this is the standard plotting library.

- uproot, a more recent library to efficiently open ROOT files, effectively freeing you from needing to install the entire ROOT package.

- awkward, also a more recent library that lets us perform fast, efficient calculations on the jagged arrays that we so often encounter in HEP datasets. More on this later…

- xrootd, a library that allows ROOT and

uprootto access files over the web, provided they are refereced in a particular way.

numpy and matplotlib are most likely already installed when you installed your Anaconda distribution. But lets test this out!

Test on your local bash terminal

Open a bash terminal (native Linux shell, Terminal on Mac, or WSL2 Linux bash shell) and type

python

If the Anaconda installation was installed properly, you should get output that looks something like

Python 3.7.9 (default, Aug 31 2020, 12:42:55)

[GCC 7.3.0] :: Anaconda, Inc. on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

You will most likely have a different version of python (perhaps 3.8 or 3.9), but it should definitely say Anaconda somewhere in that output.

In this environment, lets see if we can import some of these libraries. At the prompt (>>>), type

the following lines, hitting Enter (or Return) after you type them.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pylab as plt

If it all worked, you should see no output. If you get errors, reach out to the organizers through Mattermost.

Type quit() to exit and return to the shell.

Creating a python virtual environment

We will now use the Anaconda tools to install a

virtual environment.

This creates an environment with a specific version of python with very specific libraries installed.

By creating this environment all at once, you can often avoid some of the conflicts that cause pip to take

a long time or fail.

If you have installed Anaconda, you should be able to open a terminal or on Windows, the Anaconda command line

tool. We’ll be making use of the conda tool, provided by Anaconda. You can make sure it’s there by typing

conda --version

conda 4.12.0

You might not get that exact version, but that’s OK, so long as you get some sort of version.

You can now use conda to create a virtual environment with the modern python tools we’ll be using

for this pre-exercise and later lessons. We’ll call this environment pyhep.

conda create --name pyhep -c conda-forge root matplotlib xrootd awkward uproot numpy jupyter

It might take a while (10-20 minutes). Once it’s created, you can then type

conda activate pyhep

Now go into the python interpreter by typing python and then try typing the following in that interpreter.

import uproot

import awkward as ak

If you don’t get any errors then congratulations! You have installed the necessary libraries and are ready to perform some HEP analysis with your new python environment!

and when you use python or jupyter you’ll be able to use all these libraries. Just make sure

you first activate this virtual environment with

conda activate pyhep

Key Points

It takes a finite amount of work to be able to read and and analyze ROOT files on your laptop.

You can do this without ever using the official ROOT libraries.

Using uproot to open ROOT files

Overview

Teaching: 10 min min

Exercises: 10 min minQuestions

How do I open a ROOT file with uproot?

How do I explore what is in the file?

Objectives

Use a different library than ROOT to open ROOT files

Get comfortable with a different way of examining ROOT files

Other resources

Before we go any further, we point out that this episode and the next are only the

most basic introductions to uproot and awkward. There is a plethora of material

that go much deeper and we list just a few here.

- Official uproot documentation

- HSF uproot and awkward tutorial

- Uproot, awkward, and columnar analysis from Jim Pivarski.

How to type these commands?

Now that you’ve installed the necessary python modules you can choose to write and execute the code however you like. There are a number of options, but we will point out two here.

-

Jupyter notebook. This provides an editor and an evironment in which to run your python code. Often you will run the code one cell at a time, but you could always put all your code in one cell if you prefer. There are many, many tutorials out there on using Jupyter notebooks and if you chose to use Jupyter as your editing/executing environment that you have developed some familiarity with it.

- In the

my_pythoncontainer, you can startjupyter-labwithjupyter-lab --ip=0.0.0.0 --no-browser

and open the link given in the message on your browser. Choose the icon under “Notebook”.

- In the

-

Python scripts. In this approach, you edit the equivalent of a text file and then pass that text file into a python interpreter. For example, if you edited a file called

hello_world.pysuch that it contained

print("Hello world!")

You could save the file and then (perhaps in another Terminal window), execute

python hello_world.py

This would interpret your text file as python commands and produce the output

Hello world!

We leave it to you to decide which approach you prefer.

Open a file

Let’s open a ROOT file!

If you’re writing a python script, let’s call it open_root_file.py and if you’re using

a Jupyter notebook, let’s call it open_root_file.ipynb. If you are working in the container, you will open and edit the python script on your local computer and run it in the container, or you will open a notebook on your jupyter-lab window in the browser.

First we will import the uproot library, as well as some other standard

libraries. These can be the first lines of your python script or the first cell of your Jupyter notebook.

If this is a script, you may want to run python open_root_file.py every few lines or so to see the output.

If this is a Jupyter notebook, you will want to put each snippet of code in its own cell and execute

them as you go to see the output.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pylab as plt

import uproot

import awkward as ak

Let’s open the file! We’ll make use of uproots use of XRootD to

read in the file over the network. This will save us from having to download the file.

infile_name = 'root://eospublic.cern.ch//eos/opendata/cms/derived-data/AOD2NanoAODOutreachTool/ForHiggsTo4Leptons/SMHiggsToZZTo4L.root'

infile = uproot.open(infile_name)

Download the file?

If too many people are trying to open the same file, it may be easier to download the file to your laptop. You can execute the following command in the bash terminal.

curl http://opendata.cern.ch/record/12361/files/SMHiggsToZZTo4L.root --output SMHiggsToZZTo4L.rootAlternatively, you can follow this link to the data record on the CERN Open Data Portal. If you scroll down to the bottom of the page and click the Download button.

For the remainder of this tutorial you will want the file to be in the same directory/folder as your python code, whether you are using a Jupyter notebook or a simple python script. So make sure you move this file to that location after you have downloaded it.

To read in the file, you’ll change one line to define the input file to be

infile_name = 'SMHiggsToZZTo4L.root'

So you’ve opened the file with uproot. What is this infile object? Let’s add the following code

print(type(infile))

and we get

<class 'uproot.reading.ReadOnlyDirectory'>

We can interface with this object similar to how we would interface with a python dictionary.

keys = infile.keys()

print(keys)

['Events;1']

But what is this?

events = infile['Events']

print(type(events))

<class 'uproot.models.TTree.Model_TTree_v20'>

Ah, this is the TTree object that we learned a bit about in the previous episodes! Let’s see what’s in it!

branches = infile['Events'].keys()

for branch in branches:

print(f"{branch:20s} {infile['Events'][branch]}")

run <TBranch 'run' at 0x7faa76d2cdd8>

luminosityBlock <TBranch 'luminosityBlock' at 0x7faa76d2cda0>

event <TBranch 'event' at 0x7faa76d13748>

PV_npvs <TBranch 'PV_npvs' at 0x7faa76d13e10>

PV_x <TBranch 'PV_x' at 0x7faa76d194e0>

PV_y <TBranch 'PV_y' at 0x7faa76d19ba8>

PV_z <TBranch 'PV_z' at 0x7faa76d212b0>

nMuon <TBranch 'nMuon' at 0x7faa76d21978>

Muon_pt <TBranch 'Muon_pt' at 0x7faa76d5c080>

Muon_eta <TBranch 'Muon_eta' at 0x7faa76d5c6d8>

Muon_phi <TBranch 'Muon_phi' at 0x7faa76d5ccc0>

Muon_mass <TBranch 'Muon_mass' at 0x7faa76d582e8>

Muon_charge <TBranch 'Muon_charge' at 0x7faa76d588d0>

Muon_pfRelIso03_all <TBranch 'Muon_pfRelIso03_all' at 0x7faa76d58eb8>

Muon_pfRelIso04_all <TBranch 'Muon_pfRelIso04_all' at 0x7faa76d4e4e0>

Muon_dxy <TBranch 'Muon_dxy' at 0x7faa76d4eac8>

Muon_dxyErr <TBranch 'Muon_dxyErr' at 0x7faa7443a0f0>

Muon_dz <TBranch 'Muon_dz' at 0x7faa7443a6d8>

Muon_dzErr <TBranch 'Muon_dzErr' at 0x7faa7443ad30>

nElectron <TBranch 'nElectron' at 0x7faa74442358>

Electron_pt <TBranch 'Electron_pt' at 0x7faa74442940>

Electron_eta <TBranch 'Electron_eta' at 0x7faa74442f28>

Electron_phi <TBranch 'Electron_phi' at 0x7faa7444a550>

Electron_mass <TBranch 'Electron_mass' at 0x7faa7444ab38>

Electron_charge <TBranch 'Electron_charge' at 0x7faa74451160>

Electron_pfRelIso03_all <TBranch 'Electron_pfRelIso03_all' at 0x7faa74451748>

Electron_dxy <TBranch 'Electron_dxy' at 0x7faa74451d30>

Electron_dxyErr <TBranch 'Electron_dxyErr' at 0x7faa74459358>

Electron_dz <TBranch 'Electron_dz' at 0x7faa74459940>

Electron_dzErr <TBranch 'Electron_dzErr' at 0x7faa74459f28>

MET_pt <TBranch 'MET_pt' at 0x7faa7445f550>

MET_phi <TBranch 'MET_phi' at 0x7faa7445fbe0>

There are multiple syntax you can access each of these branches.

pt = infile['Events']['Muon_pt']

# or

pt = infile['Events/Muon_pt']

# or

pt = events.Muon_pt

# or

pt = events['Muon_pt']

We’ll use that last one for this lesson just to save some typing. :)

In the next episode we’ll use the awkward array object when we extract these data

and see how we can use awkward in a standard-but-slow way or in a clever-and-fast way!

Key Points

You can use uproot to interface with ROOT files which is often easier than installing the full ROOT ecosystem.

Using awkward arrays to analyze HEP data

Overview

Teaching: 10 min min

Exercises: 10 min minQuestions

What are awkward arrays?

How do I work with awkward arrays?

Objectives

Learn to use awkward arrays in a simple, naive way.

Learn to use awkward arrays in a much faster way, making use of the built-in functionality of the library

Why awkward?

A natural question to ask would be “Why do I have to learn about awkward? Why can’t I just use numpy?” And yes, those are two questions. :) The quick answers are: you don’t have to and you can! But let’s dig deeper.

Awkward-array is a newer python tool written by Jim Pivarski (Princeton) and others that allows for very fast manipulation of ``jagged” arrays, like we find in HEP. You definitely don’t have to use it, but we present it here because it can speed things up considerably…if you know how to write your code.

Similarly, you can of course use standard

numpyarrays for many parts of your analysis, but your data may not always fit intonumpyarrays without some careful attention to your code. In either case, you’ll want to think about how to work with your data once you get it out of your file.

Environment

We’ll assume that you have a working, modern python environmnt (3.8 or higher) and we leave it up to you whether or not you write and execute this code in a script or as a Jupyter notebook.

Numpy arrays: a review

Before we dive into awkward lets review some of the awsome aspects of numpy

arrays…and also examine their limitations.

Let’s import numpy.

import numpy as np

Next, let’s make a simple numpy array to use for our exmples.

x = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4])

print(x)

[1 2 3 4]

Numpy arrays are great because we can perform mathematical operations on them and the operation is quickly and efficiently carried out on every member of the array.

y = 2*x

print(y)

print() # This just puts a blank line between our other print statements

z = x**2

print(z)

print()

a = np.sqrt(x)

print(a)

[2 4 6 8]

[ 1 4 9 16]

[1. 1.41421356 1.73205081 2. ]

Note that in that last operation where we take the square root, we made use of a

numpy function sqrt. That function ``knows” how to operate on the elements of

a numpy array, as opposed to the standard python math library which does not know

how to work with numpy arrays.

So this seems great! However, numpy arrays break down when you have arrays

that are not 1D and cannot be expressed in a regular ``n x m” format.

For example, suppose you have two events and each event has two muons and you

want to store the transverse momentum (\(p_T\)) for these muons in a numpy array.

pt = np.array([[20.9, 12.3], [127.1, 60.2]])

x = 2*pt

print(pt)

print()

print(x)

[[ 20.9 12.3]

[127.1 60.2]]

[[ 41.8 24.6]

[254.2 120.4]]

Great! Everything looks good and we get our expected behavior!

Now, suppose there are 3 muons in the second event. Does this still work?

pt = np.array([[20.9, 12.3], [127.1, 60.2, 23.8]])

x = 2*pt

print(x)

[list([20.9, 12.3, 20.9, 12.3])

list([127.1, 60.2, 23.8, 127.1, 60.2, 23.8])]

Wait…what??? It looks like it just duplicated the entries so now it looks

like we’re storing information for 4 muons in the first event and 6 muons

in the second event! A closer looks shows us that while pt is a numpy

array, the elements are not arrays but python list objects, which behave differently.

The reason this happened is that numpy arrays can’t deal with this type of

``jagged” behavior where the first row of your data might have 2 elements

and the second row might have 3 elements and the third row might have 0 elements

and so on. For that, we need awkward-array.

Access or download a ROOT file for use with this exercise

We’ll work with the same file as in the previous lesson. If you have jumped straight to this lesson, please go back and review how to access the file over the network or by downloading it.

Open the file

Stop! If you haven’t already, make sure you have run through the previous lesson on working with uproot.

Let’s open this ROOT file!

If you’re writing a python script, let’s call it open_root_file_and_analyze_data.py and if you’re using

a Jupyter notebook, let’s call it open_root_file_and_analyze_data.ipynb.

First we will import the uproot library, as well as some other standard

libraries. These can be the first lines of your python script or the first cell of your Jupyter notebook.

If this is a script, you may want to run python open_root_file_and_analyze_data.py every few lines or so to see the output.

If this is a Jupyter notebook, you will want to put each snippet of code in its own cell and execute

them as you go to see the output.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pylab as plt

import time

import uproot

import awkward as ak

Let’s open the file and pull out some data.

# Depending on if you downloaded the file or not, you'll use either

infile_name = 'root://eospublic.cern.ch//eos/opendata/cms/derived-data/AOD2NanoAODOutreachTool/ForHiggsTo4Leptons/SMHiggsToZZTo4L.root'

# or

#infile_name = 'SMHiggsToZZTo4L.root'

# Uncomment the above line if you downloaded the file.

infile = uproot.open(infile_name)

events = infile['Events']

pt = events['Muon_pt']

eta = events['Muon_eta']

phi = events['Muon_phi']

Let’s inspect these objects a little closer. To access the actual values, we’ll see

we need to use the .array() member function.

print(pt)

print()

print(pt.array())

print()

print(len(pt.array()))

print()

for i in range(5):

print(pt.array()[i])

<TBranch 'Muon_pt' at 0x7f01513a5c88>

[[63, 38.1, 4.05], [], [], [54.3, 23.5, ... 43.1], [4.32, 4.36, 5.63, 4.75], [], []]

299973

[63, 38.1, 4.05]

[]

[]

[54.3, 23.5, 52.9, 4.33, 5.35, 8.39, 3.49]

[]

Taking a closer look at the entries, we see different numbers of values in each ``row”, where the rows correspond to events recorded in the CMS detector.

So can we use manipulate this object like a numpy array? Yes! If we’re careful about accessing the array properly.

x = 2*pt.array()

print(x[0:5])

[[126, 76.2, 8.1], [], [], [109, 47, 106, 8.66, 10.7, 16.8, 6.98], []]

When we histogram, however, we need to make use of the awkward.flatten function.

This turns our awkward array into a 1-dimensional array, so that we lose all record of

what muon belonged to which event.

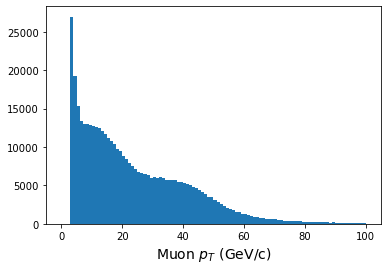

print(ak.flatten(pt.array()))

plt.figure()

plt.hist(ak.flatten(pt.array()),bins=100,range=(0,100));

plt.xlabel(r'Muon $p_T$ (GeV/c)',fontsize=14)

[63, 38.1, 4.05, 54.3, 23.5, 52.9, 4.33, ... 32.6, 43.1, 4.32, 4.36, 5.63, 4.75]

We can also manipulate the data quite quickly. Let’s see how!

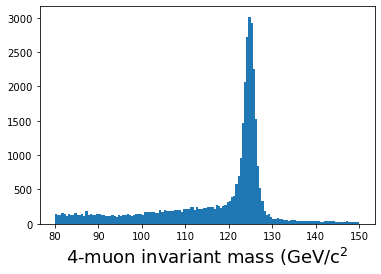

This sample file is Monte Carlo data that simulates the decay of Higgs bosons to 4 charged leptons. Let’s look for decays to 4 muons, where there are two positively charged muons and 2 negatively charged muons.

Since the data stores momentum information as \(p_T, \eta, \phi\), first we’ll calculate the Cartesian \(x,y,z\) components of momentum, and then we’ll loop over our events to calculate an invariant mass. We’ll find that looping over the entries is slow, but there is a faster way!

First the slow but explicit way.

Python code

# Some helper functions def energy(m, px, py, pz): E = np.sqrt( (m**2) + (px**2 + py**2 + pz**2)) return E def invmass(E, px, py, pz): m2 = (E**2) - (px**2 + py**2 + pz**2) if m2 < 0: m = -np.sqrt(-m2) else: m = np.sqrt(m2) return m def convert(pt, eta, phi): px = pt * np.cos(phi) py = pt * np.sin(phi) pz = pt * np.sinh(eta) return px, py, pz # Convert momentum to x,y,z components muon_number = events['nMuon'].array() pt = events['Muon_pt'].array() eta = events['Muon_eta'].array() phi = events['Muon_phi'].array() muon_q = events['Muon_charge'].array() mass = events['Muon_mass'].array() muon_px,muon_py,muon_pz = convert(pt, eta, phi) muon_e = energy(mass, muon_px, muon_py, muon_pz) # Do the calculation masses = [] nevents = len(pt) print(f"Nevents: {nevents}") start = time.time() for n in range(nevents): if n%10000==0: print(n) nmuons = muon_number[n] e = muon_e[n] q = muon_q[n] px = muon_px[n] py = muon_py[n] pz = muon_pz[n] if nmuons < 4: continue for i in range(0, nmuons-3): for j in range(i+1, nmuons-2): for k in range(j+1, nmuons-1): for l in range(k+1, nmuons): if q[i] + q[j] + q[k] + q[l] == 0: etot = e[i] + e[j] + e[k] + e[l] pxtot = px[i] + px[j] + px[k] + px[l] pytot = py[i] + py[j] + py[k] + py[l] pztot = pz[i] + pz[j] + pz[k] + pz[l] m = invmass(etot, pxtot, pytot, pztot) masses.append(m) print(f"Time to run: {(time.time() - start)} seconds") # Plot the results plt.figure() plt.hist(masses,bins=140,range=(80,150)) plt.xlabel(r'4-muon invariant mass (GeV/c$^2$',fontsize=18) plt.show()

When I run this on my laptop, it takes a little over 3 minutes to run. Is there a better way?

Yes!

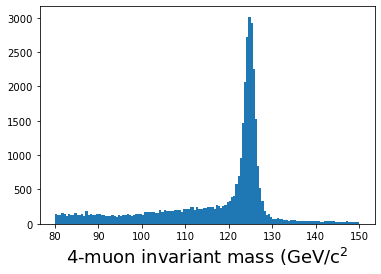

We’ve adapted some code from this tutorial, put together by the HEP Software Foundation to show you how much faster using the built-in awkward functions can be.

Python code

start = time.time() muons = ak.zip({ "px": muon_px, "py": muon_py, "pz": muon_pz, "e": muon_e, "q": muon_q, }) quads = ak.combinations(muons, 4) mu1, mu2, mu3, mu4 = ak.unzip(quads) mass_fast = (mu1.e + mu2.e + mu3.e + mu4.e)**2 - ((mu1.px + mu2.px + mu3.px + mu4.px)**2 + (mu1.py + mu2.py + mu3.py + mu4.py)**2 + (mu1.pz + mu2.pz + mu3.pz + mu4.pz)**2) mass_fast = np.sqrt(mass_fast) qtot = mu1.q + mu2.q + mu3.q + mu4.q print(f"Time to run: {(time.time() - start)} seconds") plt.hist(ak.flatten(mass_fast[qtot==0]), bins=140,range=(80,150)); plt.xlabel(r'4-muon invariant mass (GeV/c$^2$',fontsize=18) plt.show()

On my laptop, this takes less than 0.2 seconds! Note that we are making use of

boolean arrays to perform masking

when we type mass_fast[qtot==0].

While we cannot teach you everything about awkward, we hope we’ve given you a basic introduction

to what it can do and where you can find more information so that you can quickly process

the output of any of your open data jobs and get started on your own analysis!

Key Points

Awkward arrays can help speed up your code, but it requires a different way of thinking and more awareness of what functions are coded up in the awkward library.